From left, first-year medical students Shrey Kapoor, Ashish Vankara, Pranjal Agrawal and Divyaansh Raj have been helping Johns Hopkins faculty and aid organizations tackle India’s COVID-19 crisis.

Johns Hopkins Students and Faculty Members Confront India’s COVID-19 Crisis

When India’s COVID-19 cases surged in April, Pranjal Agrawal had the death of her uncle fresh in her mind. He died in August 2020 during the country’s first wave, just before Agrawal started medical school at The Johns Hopkins University.

Unable to travel home to the San Francisco Bay Area where her parents live, or to fly to India to be with family, Agrawal grieved alone in Baltimore. She thought about the stress COVID-19 put on her uncle’s lungs and heart, the pain and fear he must have felt.

“It happened so suddenly, and he was alone,” she says.

Since then, “absolutely everyone” in her family in India has been infected with the coronavirus that causes COVID-19.

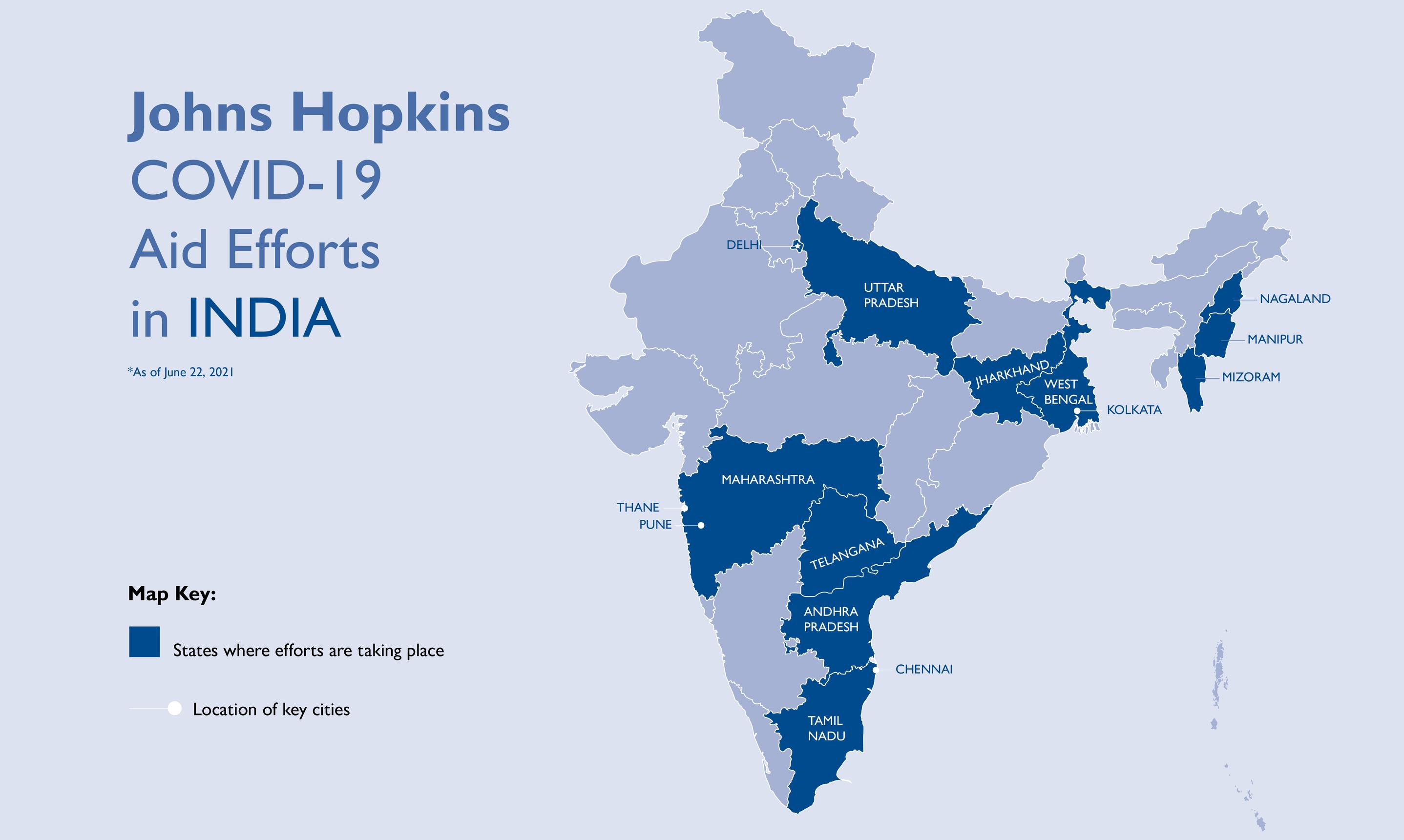

With firsthand knowledge of the trauma and grief that innumerable patients and their families were experiencing in her native country, Agrawal and several classmates started looking for ways to help in mid-April, before the outbreak in India made global headlines. Since then, the students have been filling in gaps identified by Johns Hopkins faculty members and partners on the ground, including by connecting nongovernmental organizations with resources, establishing protocols for in-home patient care in the slums of Kolkata, raising awareness about fundraisers, helping to ramp up a rapid antigen testing program and combating misinformation.

“The emotional aspect of medicine made me want to become a physician,” Agrawal says, “and India is a place that’s very, very close to my heart.”

She and her classmates became board members of the Johns Hopkins chapter of the South Asian Medical Student Association, and through the organization as well as their own contacts, they built a list of more than 70 students from over 50 medical schools throughout the U.S. They also started a group chat on WhatsApp through which needs in India are addressed.

India has the largest diaspora in the world, with 18 million people living outside of the country. Indian students were the largest subgroup of Asian applicants to U.S. medical schools for the 2018–2019 academic year, at 32.4%, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges. (Chinese applicants accounted for 15.4%, and Korean applicants 9.7%). In fall 2020, Indian students followed Chinese students as the largest group of non-U.S. citizens among combined M.D. and Ph.D. students at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

It’s not just students who are helping to fight COVID-19 in India. Much of this effort is being done in concert with the new Johns Hopkins India Institute (JHII) and its COVID-19 task force, which, like the students, is addressing priorities identified by partners in India. The task force is soliciting donations and helping to obtain oxygen supplies, personal protective equipment, lab material, testing kits and humanitarian aid by mobilizing faculty members, staff members and students from across The Johns Hopkins University and Johns Hopkins Medicine. As of June 15, JHII received 550 gifts totaling more than $1.1 million to help support nearly a dozen partner organizations in India and to buy four shipments of oxygen concentrators — portable devices that supply an oxygen-rich gas stream from surrounding air through a mask or nasal tubes.

“What’s happening in India is truly horrific,” says Amita Gupta, professor of infectious diseases at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Gupta co-chairs the JHII with David Peters, chair of the Department of International Health at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. “If India is not safe, the world’s not safe. COVID anywhere affects us everywhere, and so we can’t lay down the guard.”

The surge that started in April and peaked in early May, when India saw more than 400,000 new cases and 4,000 deaths per day, overwhelmed the country’s health care system and exhausted essential supplies. While the number of new daily cases decreased to less than 100,000 as of June 10 and some states began lifting lockdown restrictions, less than 5% of India’s adult population was vaccinated as of that date. After an unsuccessful initial vaccine rollout, the federal government announced it would take over the country’s vaccine program June 21 and provide free vaccines to all adults.

Although cases are trending downward, the country is grieving the deaths of more than 391,000 people, a number that many suspect is an underestimate due to the density of the population and the lack of infrastructure in rural areas.

Debunking Myths and Triaging Family

From the other side of the world, first-year medical student Ashish Vankara saw most of his family in India get COVID-19, including a cousin who fought for his life in the intensive care unit.

“You’re just kind of sitting here twiddling your thumbs hoping for the best,” he says, “and hoping that at least with some of the work that we’ve been doing, that we can prevent this from happening to someone else.”

The students have translated various materials into Hindi, one of the Indian government’s two official languages and the official language of many states, including instructions and videos on how to use pulse oximeters — devices placed on the fingertips that measure oxygen in the blood.

Knowing the culture, Agrawal incorporated a cultural nuance that may have otherwise gone overlooked.

“Women wear henna on their hands quite a lot, and pulse oximeters already have some standard error for darker skin,” she says. “But henna causes them to skew their results even more, and that’s not something those instruction booklets mention.” She also provided a voice-over for the Hindi video.

Infographics that students helped create serve a major purpose: combatting misinformation. Vankara says misinformation circulates especially easily on social media in India, and during the pandemic it has come from government officials, famous cricket players and religious leaders.

“There are a lot of alternative medicines that people buy into, including my own family, that might be kind of fringe or considered complementary medicine, whereas there, it can become the standard of care for some people,” Vankara says. “Below the poverty line and in the lower class, they don’t know what to believe.”

Several of Gupta’s family members in India had COVID-19. During tele-consults with them on WhatsApp, she learned that they were receiving medications that would not be recommended in the U.S., including steroids when they had normal oxygen levels. Bloodwork was also performed more frequently than needed. She shared Johns Hopkins and World Health Organization guidelines with them.

“Everybody is on social media sending around things, and people are desperate and panicked,” Gupta says. “We have so many faculty, staff and students whose families have been infected. Some have lost loved ones, and it’s really devastating because it’s been in such a short amount of time.”

Helping at Home and Abroad

In many ways, the work of JHII and the students mirrors efforts that other Johns Hopkins faculty and staff members and students have been doing in Baltimore throughout the pandemic. Last year, these initiatives included bringing tests and information to Baltimore neighborhoods hit hardest by the pandemic, providing bilingual support to Spanish-speaking patients, and distributing food and masks. During a weekly meeting convened by Johns Hopkins, Baltimore nonprofit groups shared information and resources. More recently, Johns Hopkins Medicine worked with Baltimore City and Washington, D.C., to set up vaccine clinics to reach people with less access and fewer opportunities for vaccination.

Student volunteers also helped nonprofits apply for COVID-19-related grants, while others established an organization to combat social isolation among older adults and run errands for vulnerable Baltimore residents.

Through the Johns Hopkins HEAT Corps, a volunteer-based program, Agrawal taught Baltimore public school students about COVID-19, vaccines and precautions they can take to help protect themselves. And through COVID-Related Extended Outreach, an organization started by third-year Johns Hopkins medical students to support community members during the pandemic, she checked in by telephone with patients who were unable to see their primary care doctors in person, and reported back to those doctors.

Although the pandemic created horrific situations in the U.S. and India, Agrawal and Vankara have been able to act on the devastation by answering their calling as doctors in training.

“I didn’t come to Hopkins to just sit and learn,” Vankara says. “I really came here to work on the front lines of addressing these health crises, and having the connections and the support from the faculty and administration to do initiatives like this and have real, actionable, hopeful change — I mean, it’s awesome. I’m loving the work I’ve been able to do.”