-

About

- Health

-

Patient Care

I Want To...

-

Research

I Want To...

Find Research Faculty

Enter the last name, specialty or keyword for your search below.

-

School of Medicine

I Want to...

Rock And Rho: Proteins That Help Cancer Cells Groove - 12/26/2013

Rock And Rho: Proteins That Help Cancer Cells Groove

Cells' adaptations to low oxygen conditions inside tumors promote breast cancer’s spread

Release Date: December 26, 2013

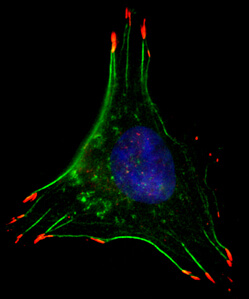

Caption: In low oxygen conditions, breast cancer cells form structures that facilitate movement, such as filaments that allow the cell to contract (green) and cellular ‘hands’ that grab surfaces to pull the cell along (red).

Credit: Daniele Gilkes

The journal article described in this news release was retracted by PNAS on Sept. 2, 2022. The retraction notice may be viewed on the PNAS website.

Biologists at The Johns Hopkins University have discovered that low oxygen conditions, which often persist inside tumors, are sufficient to initiate a molecular chain of events that transforms breast cancer cells from being rigid and stationary to mobile and invasive. Their evidence, published online in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on Dec. 9, underlines the importance of hypoxia-inducible factors in promoting breast cancer metastasis.

“High levels of RhoA and ROCK1 were known to worsen outcomes for breast cancer patients by endowing cancer cells with the ability to move, but the trigger for their production was a mystery,” says Gregg Semenza, M.D., Ph.D., the C. Michael Armstrong Professor of Medicine at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and senior author of the article. “We now know that the production of these proteins increases dramatically when breast cancer cells are exposed to low oxygen conditions.”

To move, cancer cells must make many changes to their internal structures, Semenza says. Thin, parallel filaments form throughout the cells, allowing them to contract and cellular “hands” arise, allowing cells to “grab” external surfaces to pull themselves along. The proteins RhoA and ROCK1 are known to be central to the formation of these structures.

Moreover, the genes that code for RhoA and ROCK1 were known to be turned on at high levels in human cells from metastatic breast cancers. In a few cases, those increased levels could be traced back to a genetic error in a protein that controls them, but not in most. This activity, said Semenza, led him and his team to search for another cause for their high levels.

What the study showed is that low oxygen conditions, which are frequently present in breast cancers, serve as the trigger to increase the production of RhoA and ROCK1 through the action of hypoxia-inducible factors.

“As tumor cells multiply, the interior of the tumor begins to run out of oxygen because it isn't being fed by blood vessels,” explains Semenza. “The lack of oxygen activates the hypoxia-inducible factors, which are master control proteins that switch on many genes that help cells adapt to the scarcity of oxygen." He explains that, while these responses are essential for life, hypoxia-inducible factors also turn on genes that help cancer cells escape from the oxygen-starved tumor by invading blood vessels, through which they spread to other parts of the body.

Daniele Gilkes, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow and lead author of the report, analyzed human metastatic breast cancer cells grown in low oxygen conditions in the laboratory. She found that the cells were much more mobile in the presence of low levels of oxygen than at physiologically normal levels. They had three times as many filaments and many more "hands" per cell. When the hypoxia-inducible factor protein levels were knocked down, though, the tumor cells hardly moved at all. The numbers of filaments and "hands" in the cells and their ability to contract were also decreased.

When Gilkes measured the levels of the RhoA and ROCK1 proteins, she saw a big increase in the levels of both proteins in cells grown in low oxygen. When the breast cancer cells were modified to knock down the amount of hypoxia-inducible factors, however, the levels of RhoA and ROCK1 were decreased, indicating a direct relationship between the two sets of proteins. Further experiments confirmed that hypoxia-inducible factors actually bind to the RhoA and ROCK1 genes to turn them on.

The team then took advantage of a database that allowed them to ask whether having RhoA and ROCK1 genes turned on in breast cancer cells affected patient survival. They found that women with high levels of RhoA or ROCK1, and especially those women with high levels of both, were much more likely to die of breast cancer than those with low levels.

"We have successfully decreased the mobility of breast cancer cells in the lab by using genetic tricks to knock the hypoxia-inducible factors down," says Gilkes. "Now that we understand the mechanism at play, we hope that clinical trials will be performed to test whether drugs that inhibit hypoxia-inducible factors will have the double effect of blocking production of RhoA and ROCK1 and preventing metastases in women with breast cancer."

Other authors of the report include Lisha Xiang, Sun Joo Lee, Pallavi Chaturvedi, Maimon Hubbi and Denis Wirtz of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

This work was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute (U54-CA143868), the Johns Hopkins Institute for Cell Engineering, the American Cancer Society and the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation.

For the Media

Media Contacts:

Vanessa McMains; 410-502-9410; [email protected]

Catherine Kolf; 443-287-2251; [email protected]