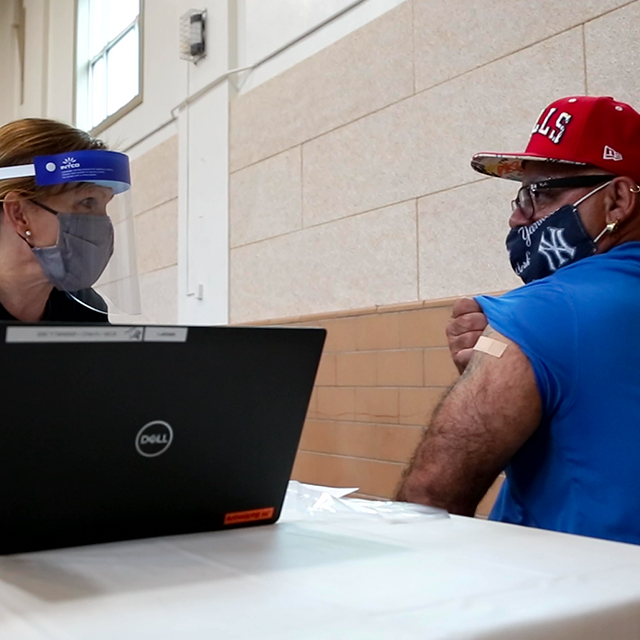

“I check to see if the family is having problems, especially this past year,” Flor Giusti, a bilingual social worker at the Children’s Medical Practice at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center. | Photo by Will Kirk

Social Worker for Hispanic and Latino Families Embodies a Duty to Serve Others

Imagine a hallway at the back of a pediatric outpatient clinic at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center buzzing with patients, parents and clinicians. A mother holding her infant knocks on the door of an office. “One moment!” says a voice from inside. Seconds later, a lean Peruvian woman with gentle smile lines and wispy auburn hair opens the door. On a typical day, she says, the scene might unfold something like this:

“Hola! Espere, por favor. (Hi! Please wait.),” says Flor Giusti, a bilingual social worker at the Children’s Medical Practice. “Estare con usted breve. Sientese. (I’ll be with you shortly. Sit down.)”

Giusti picks up the phone receiver on her desk and says she will call back as soon as the forms are ready. After making a note on a piece of paper, she turns to her visitor: “Como esta? (How are you?)”

Since the coronavirus pandemic began, Giusti has maintained an in-person presence at the Children’s Medical Practice so that she can be available to help adults who come to the clinic with their children. Along with pediatric medicine, the clinic provides integrated care for the parents.

Most of the families she sees are Hispanic (from Spanish-speaking culture or origin) or Latino (from Latin American culture or origin) and live in ZIP code 21224, where Bayview Medical Center is located. According to City-Data.com, nearly 20% of the population in this area is Hispanic or Latino.

“I check to see if the family is having problems, especially this past year,” Giusti says. “Do they have money for food? Are they receiving benefits for their children? Are they aware of the places giving COVID vaccines?”

Since taking this position in 2011, the social worker has gained extensive experience navigating ways for families to receive assistance with health insurance, food, housing and other basic needs. During normal times, these processes can be confusing. During the pandemic, Giusti says, “It’s been a nightmare to find help. With all the restrictions over the last year, nothing has been easy to obtain.”

She says she has encountered mothers who lost jobs cooking or washing dishes at restaurants, and fathers whose hours as day laborers were reduced. If the parents are immigrants without Social Security numbers, they must provide proof of employment to get government-provided resources such as food and health insurance for which their U.S.-born children qualify.

During the pandemic, many of the people Giusti helps have struggled to obtain the required papers from employers whose businesses have reduced operating hours or closed their doors.

Similarly, it has been difficult to reach the staff at government offices who help coordinate such services. “Parents need to provide proof of income and are told to mail it in, but people are not receiving the mail on the other end,” says Giusti.

Giusti helps mothers sign up for the Women, Infants and Children (WIC) food program, obtain emergency medical assistance to cover the costs of labor and delivery, and enroll newborns in health insurance.

In addition to trying to ensure the families’ needs are met, Giusti helps address the cultural barriers they face. One parent was confused when a doctor asked her to make a medical decision after the parent received all the medical information and options. The mother didn’t understand because she considers the physician to be the expert.

“They think, ‘If I could make the decision, why would I come to the doctor?’” says Giusti. “American culture places value on independence and self-sufficiency, whereas many of my families do not have this ingrained from their culture.”

Valuing Community Over Independence

Like that of the families she serves, the culture Giusti grew up in emphasized the collective group over the individual, and she learned to take other people into account when making decisions. She and her 10 brothers and sisters witnessed their father, a pediatrician, serve low-income families in his hometown of Callao, Peru. Every major decision he made, says Giusti, came from a commitment to social justice that was rooted in his strong Catholic faith.

“We got this sense that we have to make this world better,” says Giusti. “That was the most important thing in our family. Are you doing something for you, or are you doing something for you as part of a community?”

Unlike the families she serves, Giusti and all of her siblings attended college in Peru. At one point, five were enrolled in a private university simultaneously. To soften the financial burden, her father took a second job at the school to receive tuition reductions. “We didn't have excesses, but we did have a comfortable life,” says Giusti. “There was food on the table and we lived in a very nice neighborhood. We each had one pair of shoes for winter and one pair of shoes for summer.”

Many of the families Giusti works with left places of violence and then endured unsafe travel to enter the U.S., but they were willing to take the risk. “They made it here, and they feel they need to survive,” she says. “They keep going, no matter how hard it gets.”

After completing her education, Giusti was a psychologist in Lima — a profession similar to social worker in the U.S. In 1991, when her husband decided to pursue a master’s degree in public health from The Johns Hopkins University, the couple and their 5-year-old son immigrated to Maryland.

To continue her career in the U.S., Giusti earned a master’s degree from the University of Maryland. She started working in Baltimore at an organization that helped Hispanic and Latino women affected by domestic violence. One of the biggest lessons she learned was the importance of supporting them to take the next steps toward gaining independence, she says. This included showing women that she was there for them — in big and small ways — so they would feel confident that even if something terrible happened, they would not be alone.

“Eventually, it would get to the point that the women would see they don’t need to put up with their abuse, because they know they have a way to get help,” Giusti says. “In the Latino culture, as in many other cultures in the world, self-sufficiency is not necessarily a value.”

In her role at the Hopkins Bayview pediatric outpatient clinic, Giusti also provides counseling for people experiencing depression as well as domestic violence, helps facilitate parenting classes and a support group for parents of children on the autism spectrum, and serves on the Latino Family Advisory Board. In addition, she gives presentations about cultural sensitivity to John Hopkins medical students and faculty and staff members.

“You don’t even realize that cultural differences can get in the way,” she says. “Is the message you are trying to convey actually the message that the other person is hearing?”

Giusti volunteers with the Center for Salud/Health & Opportunities for Latinos (Centro SOL), which promotes equity in health and opportunity for Latinos by advancing clinical care, research, education and advocacy at Johns Hopkins in partnership with its Latino neighbors. Through Centro SOL, she helps facilitate Testimonios, a mental health support group. In 2016, Giusti won the Inspired to Inspire award issued by then Baltimore mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake.

By addressing the social determinants of health — the conditions in which families live and work that affect how they function and their quality of life — Giusti strives to improve the lives of underserved groups, a duty inspired by her father’s example. “We don’t live in a world that is just,” she says. “We don't choose when or where we are born, what kind of culture, race, socioeconomic status or family we are born into. The need for social justice is there every day.”